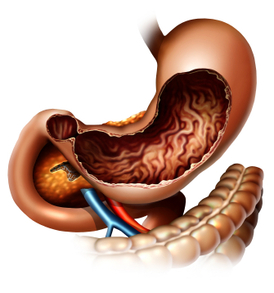

Stomach cancer is referred to as gastric cancer. The most common type of gastric cancer is called adenocarcinoma. This starts in the glandular tissue that composes the lining of the stomach and accounts for 90% to 95% of all gastric cancers. Other forms of gastric cancer include lymphomas, which involve the lymphatic system and sarcomas, which involve the connective tissue (such as muscle, fat, or blood vessels).

Generally, the best chance for cure of gastric cancer is when it is found and treated at a very early stage. Unfortunately, the outlook is typically poor if the cancer is already at an advanced stage when discovered.

Gastric cancer can develop in any part of the stomach and may spread throughout the stomach and to other organs, such as the esophagus, liver and lungs. Gastric cancer is responsible for about 800,000 deaths worldwide per year.

The signs/symptoms include indigestion and/or heartburn, loss of appetite, especially for meat, abdominal discomfort or irritation, weakness and fatigue, bloating of the stomach, usually after meals, abdominal pain in the upper abdomen, nausea and occasional vomiting, diarrhra or constipation, weight loss, vomiting, blood in the stool, which will appear as black. This can lead to anemia, and dyspagia (trouble swallowing), which suggests a tumor in the upper protion of the stomach or extension of the gastric tumor into the esophagus.

The diagnosis is typically made when abnormal tissue seen in a direct visual (gastroscopic) examination is biopsied. This tissue is then examined under a microscope to check for the presence of cancerous cells. A biopsy, with subsequent histological analysis, is the only sure way to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

The clinical stages of stomach cancer are:

Stage 0. Limited to the inner lining of the stomach.

Stage I. Penetration to the second or third layers of the stomach (Stage 1A) or to the second layer and nearby lymph nodes (Stage 1B).

Stage II. Penetration to the second layer and more distant lymph nodes, or the third layer and only nearby lymph nodes, or all four layers but not the lymph nodes.

Stage III. Penetration to the third layer and more distant lymph nodes, or penetration to the fourth layer and either nearby tissues or nearby or more distant lymph nodes.

Stage IV. Cancer has spread to nearby tissues and more distant lymph nodes, or has metastatized to other organs.

Treatment for gastric cancer depends on both the tissue type and the stage of the cancer. Treatment for adenocarcinoma may include:

1. Surgery– the goal of surgery is to remove all of the cancer and allow for a margin of healthy tissue, when possible. The surgeon also removes lymph nodes surrounding the stomach to determine if they have been invaded by cancer cells. Removing part of the stomach may relieve signs and symptoms of a growing tumor in people with advanced stomach cancer. In this case, surgery generally does not cure the cancer, but it can make the patient more comfortable. This is known as palliative therapy.

2. Radiation Therapy-uses high-powered beams of energy to kill cancer cells. It can be used before surgery (neoadjuvant radiation) to shrink a stomach tumor so it’s more easily removed. Radiation therapy can also be used after surgery (adjuvant radiation) to kill any cancer cells that might remain. Radiation is often combined with chemotherapy. In cases of advanced cancer, radiation therapy may be used to relieve side effects caused by a large tumor. Radiation therapy can cause diarrhea, indigestion, nausea and vomiting.

3. Chemotherapy-is a drug treatment that uses chemicals to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy drugs can kill cancer cells that may have spread beyond the stomach. Chemotherapy can be given before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to help shrink a tumor so it can be more easily removed. And it can be given after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) to kill any cancer cells that might remain in the body. Chemotherapy is often combined with radiation therapy. Chemotherapy may be used alone in patients with advanced stomach cancer to help relieve signs and symptoms. Side effects of chemotherapy depend on which drugs are used, and which drugs are used depends upon the type of cancer being treated.

4. Clinical Trials-are always being done at research cancer centers to study new treatments and new ways of using existing treatments. Participating in a clinical trial may give a patient a chance to try the latest treatments. In some cases, researchers might not be certain of a new treatment’s side effects.

Depending on the stage at diagnosis, the average 5 year survival rates for adenocarcinoma of the stomach are as follows:

Stage Ia – 71%

Stage Ib – 57%

Stage IIa – 45%

Stage IIb – 33%

Stage IIIa – 20%

Stage IIIb – 14%

Stage IV – Less than 4%.

Medical malpractice may be seen when there is a significant and negligent delay in the diagnosis of gastric cancer. As the above shows, if the diagnosis is delayed, and the stage advances, the prognosis for 5 year survival rates becomes poor. During patient screening, a doctor should be aware of the risk factors for gastric cancer that include smoking cigarettes, a diet high in salted, smoked, pickled meats or foods, stomach inflammation, a history of Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric polyps, pernicious anemia, and a family history of one or more relatives diagnosed with gastric cancer. Screening for one type of adenocarcinoma called HDGC or Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer includes genetic testing for the CDH1 gene mutation. In families with the CDH1 gene mutation, intense surveillance may be appropriate and in some cases prophylactic gastrectomy.

Aside from upper endoscopy, other helpful diagnostic tests for gastric cancers include a double contrast barium x-ray, ultrasound, or a CT scan; however, a negative barium x-ray study alone may give false assurance and is sometimes a reason for a delay in diagnosis. Research suggests that improvement in five-year survival requires not only improved awareness by patients, but especially improved diagnostic methods and screening programs by their doctors.