Posted by Dr. Larry Leichter on April 15, 2018

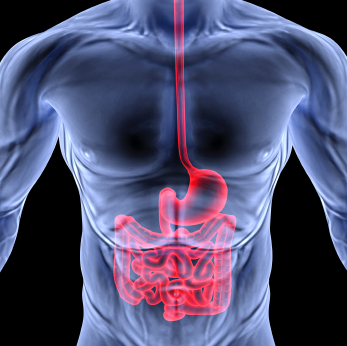

The small bowel is a long coiled hollow tube, called a tract, that is approximately twenty-five feet long. It includes the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. A small bowel obstruction, also known as a small intestinal obstruction, is a mechanical or functional (paralytic) blockage of the intestinal tract, which prevents the normal transit of digestive products. It can occur at any level throughout the jejunum and ileum, and is considered a medical emergency when it occurs. The condition is often treated conservatively for the first several days; however, the patient must be monitored very closely for signs of clinical deterioration that can become life threatening.

Mechanical obstruction is due to a mechanical barrier, such as an adhesive band from prior surgery, which creates a road block to the bowel. On the other hand, functional obstruction is caused by an event that interferes with the nervous innervation of the bowel, such as electrolyte imbalances and metabolic disturbances. Functional bowel obstruction can be caused by a multitude of conditions whereas mechanical SBO is generally credited to a luminal, mural, or extra-mural mechanical barrier. A clinical syndrome exists called small intestinal pseudo-obstruction, which is characterized by manifestations of mechanical bowel obstruction in the absence of an obstructive lesion.

The symptoms of a mechanical small bowel obstruction include abdominal fullness and/or excessive gas, abdominal distention, pains and cramps in the stomach area (specifically the mid abdomen), vomiting, constipation (inability to pass gas or stool), diarrhea, and bad breath. Acute functional small bowel dilatation is referred to as adynamic or paralytic ileus. The symptoms of paralytic obstruction, in reference to the ileus, are abdominal fullness and/or excessive gas, abdominal distention, and vomiting after eating. The pain less closely resembles the colicky type seen in mechanical obstruction, but may be just as severe.

The diagnosis is determined by listening to the abdomen with a stethoscope. High-pitched, tinny and clanking sounds can be heard at the onset of mechanical obstruction. If the blockage persists for too long or the bowel is significantly damaged, due to the stretching of the blood vessels supplying it thereby decreasing blood flow, bowel sounds will decrease and eventually become silent. The hallmark of paralytic ileus is decreased or absent bowel sounds, which can create confusion in relation to the issue of etiology if this occurs.Diagnostic tests that demonstrate obstruction include plain radiographic film of the abdomen (usually in the flat and upright position), CT scan, barium enema and upper GI series with small bowel follow through.

Treatment depends on the cause of the obstruction. In some cases, drastic measures are necessary to save a person’s life, while in others a strategy of watchful waiting is more appropriate. In general, more serious cases that require immediate treatment can be identified based on a patient’s vital signs and physical exam. If the person is very sick and appears to be on the brink of a serious event, surgery may be required to ensure the patient’s life.

To determine if there is any deterioration consistent with lack of blood flow, which leads to bowel ischemia, gangrene, perforation, septic shock, and death, it is imperative that the following steps be taken. The bowel must be decompressed with a long indwelling tube, all oral feeding must be stopped and IV therapy must be initiated with continuous monitoring and observation. Generally speaking, there is no reason anyone presenting to the emergency room with a small bowel obstruction should die in the hospital unless there are extenuating circumstances.